Experiment #2: Jumping through Hoops

A playful invitation with a deeper political message about how society requires us to jump through hoops to have access to basic rights, social care and security

ACTION

Three performers wearing high-viz vests hold hula hoops and stand in a line in the pedestrianised shopping precinct of Cabot Circus and Broadmead in Bristol. The performers invite passing pedestrians to climb through the hoops as they go past. They either ask the question “would you like to jump through these hoops?” or gently indicate the pathway through the hoop in silence but with a smile. For those who accept the invitation they bend down and climb through each hoop, that may be lifted or lowered to make the journey harder or easier. The hoop jumper is ‘assessed’ by a performer dressed in medical scrubs placed at the end who gives them a ‘pass’ or ‘fail’ written on a piece of paper. Three performers are plants pretending to be everyday public and agree to participate in invited action to encourage other members of public to join in. One of the plants is disabled and walks with crutches. She asks for assistance from people passing by, seeking advice on the best way to climb through or demonstrations on the best approach. The action happens at three locations; one inside Cabot Circus Mall and two places on Broadmead; one in an open section of the path and the second where the path narrows making it more difficult to avoid the line of hoops.

Three performers wearing high-viz vests hold hula hoops and stand in a line in the pedestrianised shopping precinct of Cabot Circus and Broadmead in Bristol. The performers invite passing pedestrians to climb through the hoops as they go past. They either ask the question “would you like to jump through these hoops?” or gently indicate the pathway through the hoop in silence but with a smile. For those who accept the invitation they bend down and climb through each hoop, that may be lifted or lowered to make the journey harder or easier. The hoop jumper is ‘assessed’ by a performer dressed in medical scrubs placed at the end who gives them a ‘pass’ or ‘fail’ written on a piece of paper. Three performers are plants pretending to be everyday public and agree to participate in invited action to encourage other members of public to join in. One of the plants is disabled and walks with crutches. She asks for assistance from people passing by, seeking advice on the best way to climb through or demonstrations on the best approach. The action happens at three locations; one inside Cabot Circus Mall and two places on Broadmead; one in an open section of the path and the second where the path narrows making it more difficult to avoid the line of hoops.

AUDIENCE RESPONSE

There is a mixed response from the public. Some participate, some watch and some walk around to avoid the performers. A couple of young men walking past see the game and run over to climb through. Some curious members of public and come over and ask what is going on. Parents encourage children to run through but most will not climb through themselves. At one point a family group with 6 small children stop to play, with the children running continually through the tunnel of hoops, enjoying the game while their mother enjoys a small rest. Our disabled performer asks for help as she climbs through and receives it from passers by. “Some were kind enough to assist myself through hoops and demonstrate (with my crutches) how to get through”. The physical act of navigating through the three hoops by members of public and the ‘plants’ becomes a spectacle for others who stop to look. A couple watching from a bench applaud the success of participants. A performer notes that “people want a distraction and to play.” For most spectators the overall message is unclear, “I’m confused though, I don’t understand” says one participant who has completed the task and receives an assessment. Another asks “what benefits am I getting?” the answer to which we do not have.

There is a mixed response from the public. Some participate, some watch and some walk around to avoid the performers. A couple of young men walking past see the game and run over to climb through. Some curious members of public and come over and ask what is going on. Parents encourage children to run through but most will not climb through themselves. At one point a family group with 6 small children stop to play, with the children running continually through the tunnel of hoops, enjoying the game while their mother enjoys a small rest. Our disabled performer asks for help as she climbs through and receives it from passers by. “Some were kind enough to assist myself through hoops and demonstrate (with my crutches) how to get through”. The physical act of navigating through the three hoops by members of public and the ‘plants’ becomes a spectacle for others who stop to look. A couple watching from a bench applaud the success of participants. A performer notes that “people want a distraction and to play.” For most spectators the overall message is unclear, “I’m confused though, I don’t understand” says one participant who has completed the task and receives an assessment. Another asks “what benefits am I getting?” the answer to which we do not have.

REFLECTIONS AFTER THE ACT

As a group, our main reflection after the act was that our message was not clear but the task was. This came down to the lack of time for the group to get on the same page with the action we were going to create. Our first proposal was to create a set of difficult or impossible tasks that we would put the disabled performer through. However as a group we felt that it would give a strong message but not one that everyone felt clear on “The subjects can be very sensitive and so I felt uncomfortable to have a voice on something I knew so little about.” We decided to simplify the task and generalise the message so that the whole group felt comfortable enacting it. Our theme and message then became physical act of the idiom “jumping through hoops”. This produced a paradoxical action, the fun game with a serious political commentary on passing or failing benefit assessments.

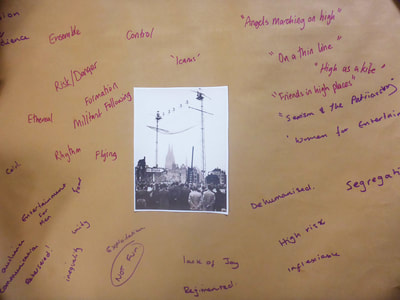

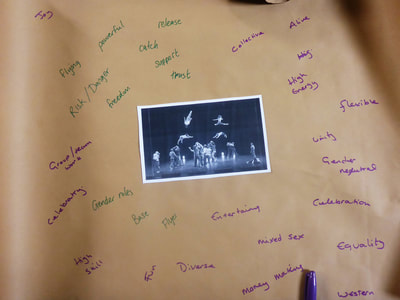

In the workshop the group explored images of circus act in order to uncover themes, idioms and political implications inherent in them. A knife thrower and his assistant inspired a conversation about gender politics. Another pair compared two images; one of acrobats flying though the air and another of militant looking tight-wire walkers high above a cityscape. The exercise fed into a brainstorming exercise and inspired lateral thinking from which we arrived at the idiom of ‘jumping through hoops’. One participant noted that the exercise allowed the circus “metaphors exist as a tool, rather than a trope”. The circus was also referenced by the use of hula hoops which was recognisable and had the connotation of playfulness and fun.

As a group, our main reflection after the act was that our message was not clear but the task was. This came down to the lack of time for the group to get on the same page with the action we were going to create. Our first proposal was to create a set of difficult or impossible tasks that we would put the disabled performer through. However as a group we felt that it would give a strong message but not one that everyone felt clear on “The subjects can be very sensitive and so I felt uncomfortable to have a voice on something I knew so little about.” We decided to simplify the task and generalise the message so that the whole group felt comfortable enacting it. Our theme and message then became physical act of the idiom “jumping through hoops”. This produced a paradoxical action, the fun game with a serious political commentary on passing or failing benefit assessments.

In the workshop the group explored images of circus act in order to uncover themes, idioms and political implications inherent in them. A knife thrower and his assistant inspired a conversation about gender politics. Another pair compared two images; one of acrobats flying though the air and another of militant looking tight-wire walkers high above a cityscape. The exercise fed into a brainstorming exercise and inspired lateral thinking from which we arrived at the idiom of ‘jumping through hoops’. One participant noted that the exercise allowed the circus “metaphors exist as a tool, rather than a trope”. The circus was also referenced by the use of hula hoops which was recognisable and had the connotation of playfulness and fun.

Time was short and half the participants noted that they would have liked more time to prepare before going onto the street. But everyone agreed much of the discoveries happened there. One participant noted that her perception of certain members of the public was challenged, “There was a woman who looked to me that she wouldn’t participate and I found myself reluctant to ask her to but I challenged myself to make contact and she did go through the hoop”. In terms of developing the work, the group agreed that it was useful to test the action to see what worked, what did not and what the public reception was like. Clearly the lack of a message or take home for the audience was an issue but the group came up with ideas to develop the piece including having information on the back of the assessor’s sheet that she gives the public.

For me the most effective and revealing aspects of the action was its simplicity. The task was easy to read and people were happy to participate without knowing what it was about. If they did not want to participate they smiled as they went around. This task encouraged participation, addressing the idea of doing the action 'with' the audience, rather than 'at' them and it created a spectacle for others.

For me the most effective and revealing aspects of the action was its simplicity. The task was easy to read and people were happy to participate without knowing what it was about. If they did not want to participate they smiled as they went around. This task encouraged participation, addressing the idea of doing the action 'with' the audience, rather than 'at' them and it created a spectacle for others.

THE WORKSHOP

PART ONE - games and physical exploration to get to know each other, build trust and complicity

PART ONE - games and physical exploration to get to know each other, build trust and complicity

PART TWO - we explored source material on creative protest and shared our findings. Then we broke into three groups to look at circus images to explore the themes, metaphors and political implications of each. After lunch we quickly looked at types of street theatre and tactics used in protest. This was followed by a brainstorming session of potential 'acts of resistance', blue-sky thinking and then what would be feasible immediately. The group share ideas and collectively discussed what action we would like to do. The debate centred two similar ideas around benefits and how they affect the vulnerable in society. The negotiation took some time to ensure everyone was comfortable with the action and authentically representing the 'message'.

PARTICIPANT FEEDBACK

There were six women and one man present at the workshop. 28% were aged between 16 and 30, 58% aged between 31 and 45 and 14% were 45+. The participants were mainly connected to circus; a mix of performers teachers, students and directors. There was also a musician and an activist present.

The majority of participants had had experience of circus and street theatre. Everyone had experience of watching circus while 87% had direct experience learning skills or performing. The brainstorming exercises using circus images provided participants with new insights; different ways of exploring circus and revealing the political. One participant said they had discovered “lots of insights through looking at photos and thinking about what issues might be in a wider context”. In application, another noted that you could use circus “to tell another story, away from the traditional aspect” while another said the exploration of circus metaphors highlighted how they could “exist as a tool, rather than a trope”.

Everyone had seen street theatre of some form before and 57% of participants had previously performed on the street in some capacity. The biggest learning curve for participants had been directly on the street where they gained new insights about performing in public space; “play invites people of all ages to engage”, “reading people is super important” and the “public are very helpful towards people with disabilities”. While another noted that her own prejudices had been challenged; “I was reluctant to ask certain people to join in because I thought they would say no. But I did ask and they joined in!”

All the participants had had experience of protest in some form or another. Most had participated in public marches and demonstrations. The process and experience provided new insights about protest. A few made comments on smallness and simplicity, “Simple acts bring responses”, “it can be small” and “creativity, novelty, simplicity is key”. Another noted that she learned “how to engage members of the public in something that is more than entertainment” while it raised a number of other questions with regards to her practice; “how do you still ‘perform’ whilst protesting? At what point are you a performer or a non performing person when staging something? At what point is my character speaking as me or as the person I am playing? When is it personal?”

Every participant had found a different element inspiring and applicable for their future work. For some the brainstorming process had provided some useful tools and theory including “the chart of what kind of street ‘performance’ already exists” and showed another “how quickly a piece can be devised and shown.” Agreeing on a common issue became a sticking point in the process. It also provided useful insights about working with issues very quickly in this way; “It can feel slightly forced and less authentic when it feels like you are fighting for someone else’s cause. It’s so personal!”

This raised a point shared by 70% of the participants, that the process was too quick and they would like more time. This related to having more time for discussions, for brainstorming and rehearsing as well as experimenting on the street.

There were six women and one man present at the workshop. 28% were aged between 16 and 30, 58% aged between 31 and 45 and 14% were 45+. The participants were mainly connected to circus; a mix of performers teachers, students and directors. There was also a musician and an activist present.

The majority of participants had had experience of circus and street theatre. Everyone had experience of watching circus while 87% had direct experience learning skills or performing. The brainstorming exercises using circus images provided participants with new insights; different ways of exploring circus and revealing the political. One participant said they had discovered “lots of insights through looking at photos and thinking about what issues might be in a wider context”. In application, another noted that you could use circus “to tell another story, away from the traditional aspect” while another said the exploration of circus metaphors highlighted how they could “exist as a tool, rather than a trope”.

Everyone had seen street theatre of some form before and 57% of participants had previously performed on the street in some capacity. The biggest learning curve for participants had been directly on the street where they gained new insights about performing in public space; “play invites people of all ages to engage”, “reading people is super important” and the “public are very helpful towards people with disabilities”. While another noted that her own prejudices had been challenged; “I was reluctant to ask certain people to join in because I thought they would say no. But I did ask and they joined in!”

All the participants had had experience of protest in some form or another. Most had participated in public marches and demonstrations. The process and experience provided new insights about protest. A few made comments on smallness and simplicity, “Simple acts bring responses”, “it can be small” and “creativity, novelty, simplicity is key”. Another noted that she learned “how to engage members of the public in something that is more than entertainment” while it raised a number of other questions with regards to her practice; “how do you still ‘perform’ whilst protesting? At what point are you a performer or a non performing person when staging something? At what point is my character speaking as me or as the person I am playing? When is it personal?”

Every participant had found a different element inspiring and applicable for their future work. For some the brainstorming process had provided some useful tools and theory including “the chart of what kind of street ‘performance’ already exists” and showed another “how quickly a piece can be devised and shown.” Agreeing on a common issue became a sticking point in the process. It also provided useful insights about working with issues very quickly in this way; “It can feel slightly forced and less authentic when it feels like you are fighting for someone else’s cause. It’s so personal!”

This raised a point shared by 70% of the participants, that the process was too quick and they would like more time. This related to having more time for discussions, for brainstorming and rehearsing as well as experimenting on the street.

ABOUT ROBYN

Robyn is a Bristol-based director, teacher and performer. With over 20 years experience she is a passionate practitioner of clowning, physical theatre, circus and street arts. She has a MA in Circus Directing, a Diploma of Physical Theatre Practice and trained with a long line of inspiring teachers including Holly Stoppit, Peta Lily, Giovanni Fusetti, Bim Mason, Jon Davison, Zuma Puma, Lucy Hopkins and John Wright.

Over the past five years she has been exploring the meeting point of clowning and a deep desire to address the injustices in the world. This specialism has developed through her Masters Research ‘Small Circus Acts of Resistance’, on the streets and in protests with the Bristol Rebel Clowns and in research residencies with The Trickster Laboratory. Robyn’s Activist Clown research has led to collaborations with Jay Jordan (Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination, France), Clown Me In (Beirut), LM Bogad (US), Hilary Ramsden (Greece) and international Tricksters; ‘The Yes Men’ (US). During the pandemic in 2020, Robyn set up The Online Clown Academy with Holly Stoppit and developed a series of Zoom Clown Courses. Robyn’s research, started during her Masters, has been exploring the meeting point of clowning and activism, online, in the real world and with international collaborators. With this drive to explore political edges of her work she has also dived back into the world of the Bouffon; training with Jaime Mears, Bim Mason, Nathaniel Justiniano, Eric Davis, Tim Licata, Al Seed and the grand master Bouffon-himself; Philippe Gaulier. Keen to explore the intersection of clowning and politics, Robyn is driven to create collaborative, research spaces, testing and pushing the limits of the artform to create new knowledge and methodologies for her industry and strengthen partnerships for future work. Some of her most recent collaborations and teaching projects have included the Nomadic Rebel Clown Academy (5-day Activist Clown Training), The Laboratory of the Un-beautiful (Feminist Grotesque Bouffon Training for Womxn Theatre Makers) and the Clown Congress (annual gathering of clowns, activists & academics collectively exploring what it means to be a clown in this current era) |