|

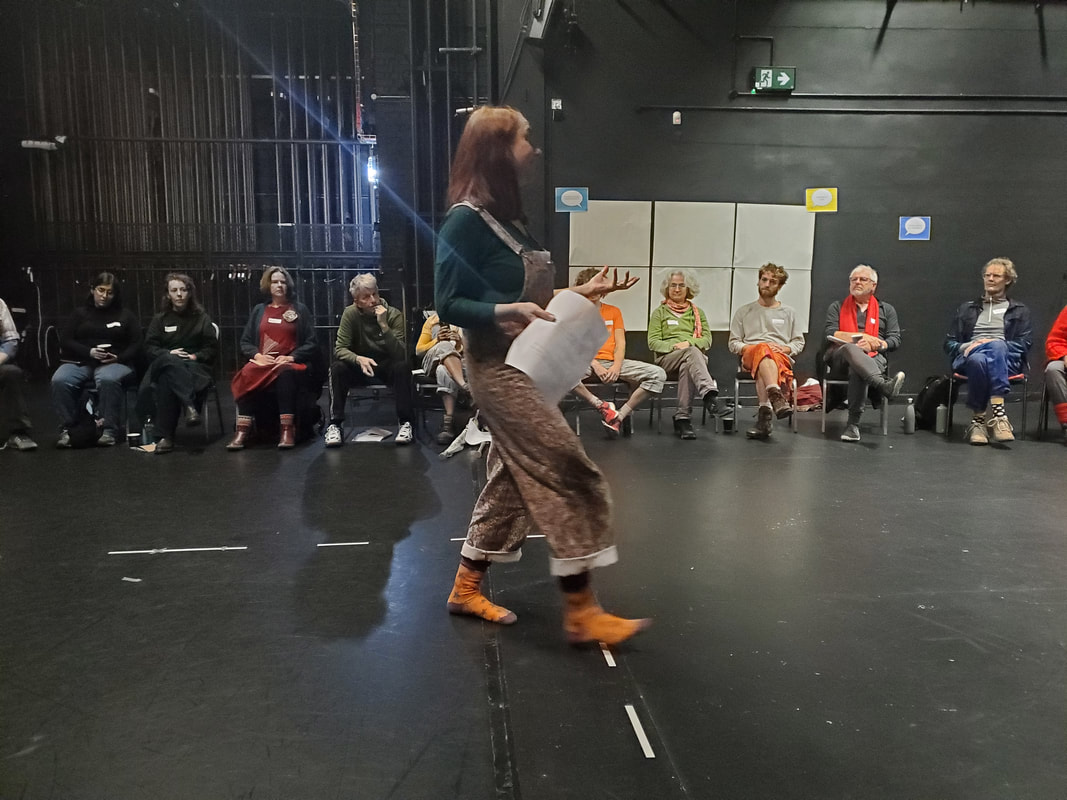

by Holly Stoppit Greetings dear reader! Holly Stoppit here, with a blog all about day one of the Clown Congress 2023. If you don’t already know me, hello! I am a clowning and fooling teacher, process facilitator, dramatherapist, autobiographical theatre director and recently qualified Internal Family Systems (IFS) practitioner. I was at the Clown Congress as a facilitator, helping to hold the space and offering Creative Clarity workshops at the end of each day. This blog focuses on the thought-provoking sessions from two of our wonderful guest contributors, Saskia Solomons and Jeremy Linnell. A Little Context The theme for this year’s Clown Congress was CLOWNS & IDENTITY; Exploring Difference in Clowning. The invitation was for a bunch of clowns from all different backgrounds to come together for three days in October, to attend a range of workshops, talks and discussions exploring “…how our differences and who we are impact the way we clown...” The invitation was to “… explore how clowning is influenced by our individuality and how society sees us today.” (Clown Congress Blurb) Send In The Clowns! A pick and mix assortment of 50+ clowns of all shapes, sizes, ages and backgrounds shuffled, shimmied and stormed their way into Bristol University’s drama department. There were clowns who work in hospitals, clowns who perform in theatres, circuses and streets, clowns who teach other clowns, clowns who disrupt the status quo with clown activism and the clown curious. Session 1: Multiple Me's: Parts Based Clown The first session was presented by Saskia Solomons, a Lecoq-trained clown-idiot, physical theatre performer, deviser, storyteller and facilitator. Saskia is also an Internal Family Systems (IFS) practitioner. If you’re not familiar with IFS, this is my take: IFS is a therapeutic system which is based on the theory that we are all made up of many parts (ie feelings, sensations, thoughts, memories, dreams, fantasies…). In an IFS session, people are guided to investigate their inner parts, to find out where the parts live in or around the body, to discover what their roles are, how the parts feel about their roles and what their fears are. Through this exploration, people can develop a more compassionate relationship with their parts, which in turn can enable parts to let go of their burdensome roles, which frees up the bound-up energy in the system. Saskia has been exploring how IFS combines with clowning in her/their recent Edinburgh Fringe solo show, ‘Fool’s Gold.’ Their Clown Congress workshop was based on some of the processes they’ve been developing, described in the programme as follows: “In this short, practical intro workshop, we will welcome our multiple inner selves into the room. Through introspective listening, embodied play, witnessing and reflection, the theme of ‘identity’ (or rather, identities) will be explored: who on the inside wants to be seen? Who is ready to play? Who is hiding under the table? And how can listening and responding to our inner needs and desires develop a ‘clownspace’ founded on internal consent, freedom and delight?” The Art of Noticing

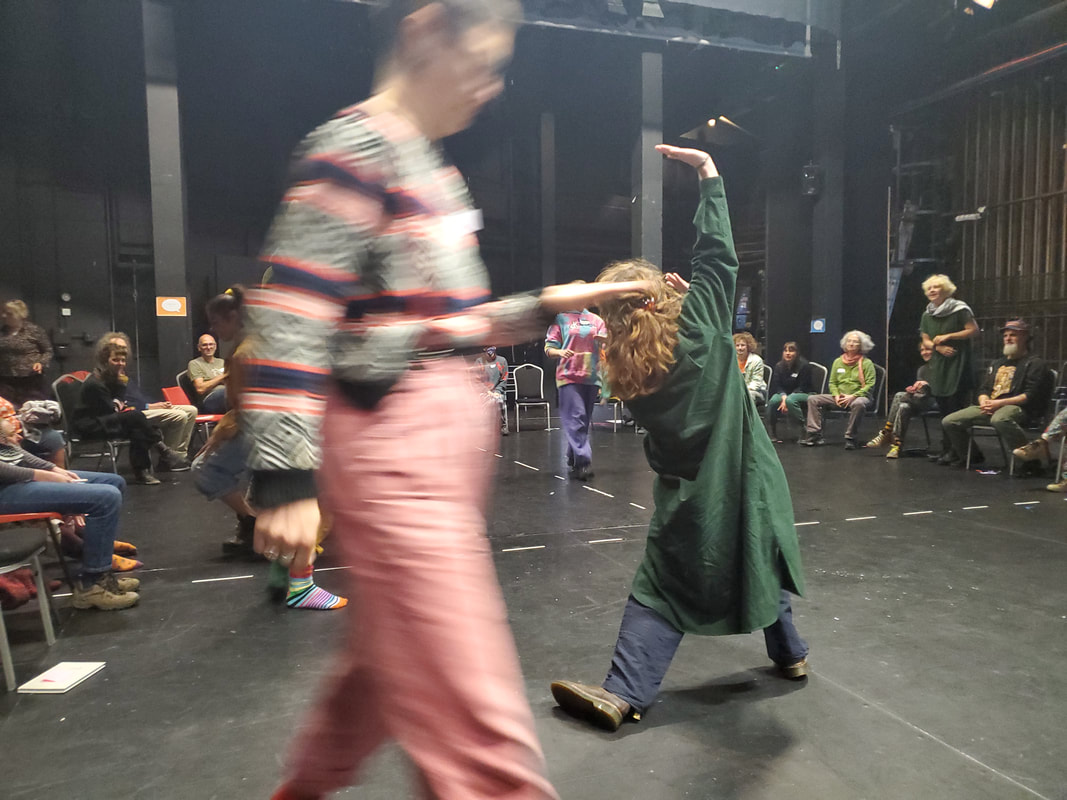

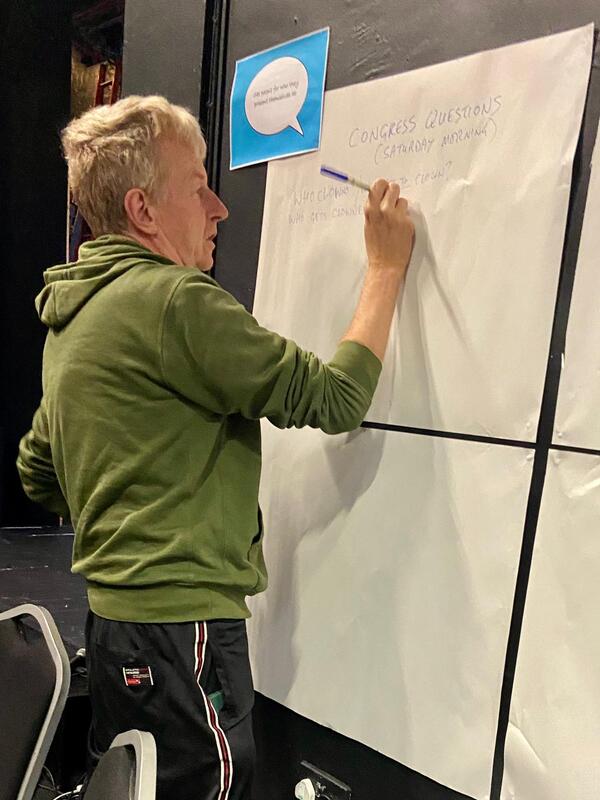

My Tuppenceworth I experienced Saskia’s holding as gentle and clear and saturated in permission for everyone to genuinely choose their own path through the workshop. There were people who dived in, embodying their parts loudly and confidently and there were other people huddled in corners, looking a bit frightened (to me the whole room looked like it could be any one of us, with all the people representing the many conflicting parts inside). Saskia validated everyone’s experiences, naming the various energies that they could perceive and offering invitations for everyone to notice and include whatever was going on for them. I was really happy that Saskia’s session was the first session of the congress, in that it seemed to give everyone a chance to consciously land into the experience of being in a massive room full of clowns. For some of the clowns, this was the first time they’d been in a big social situation since before Covid, but even for the mega sociable clowns, stepping into a huge room full of 50+ peers / strangers / professional show-offs can be daunting to say the least! Saskia’s workshop gave structured opportunities for people to get curious and conscious about their feelings and sensations around coming into a strange space and entering into connection. I feel like this laid a foundation of consciousness, curiosity and permission for the rest of the Clown Congress. The workshop was almost entirely practical, Saskia chose to not go into the IFS theory and this seemed totally appropriate to me. Saskia’s pedagogy is based in the body and creativity, so it seemed right that delegates could get to experience the method through their bodies and creativity and find out from the inside what it could do for them. Saskia held a small group discussion later in the day during the Open Space session, where they discussed the various possible applications of this method. I wasn’t at the discussion, but I can post a link to the notes here once they are live. I’m excited about this work. I can see it being incredibly useful for clowns / performers / actors / directors in the rehearsal room, by helping them to access their intuition, work with feelings that block the creative process and generate material for performance. I can also see it being useful in live performance, helping clowns and improvisers to access and play with their authentic feelings, which in my experience, makes for a very deep and resonant quality of connection with self, other players and the audience, which in turn, makes for a vibrant, resonant quality of unforgettable improvisation. Session 2: Disability & Art – The Pressure to Make Art About Your Lived Experience The second session was led by Jeremy Linnell, a neurodiverse & disabled bouffon based performance artist / live game designer / all round professional idiot and curator of mischief from Cardiff. Jeremy’s session explored the following provocation: “In the creative industries it seems there is an implicit pressure on those in marginalised groups to make work about their “lived experience” – a pressure that reduces them to their protected characteristic and often involves some degree of trauma. Does this pressure exist? Should it?” Jeremy offered a series of provocations, followed by big group discussion, interspersed with Bouffon games. This report focuses on Jeremy’s provocations and the discussion, as there were so many great points being made. I was handwriting notes as quickly as I could and I didn’t capture who said what, but here’s the gist of what was said.  Trauma Tourism / Trauma Porn Jeremy introduced us to the notion of “Trauma Tourism,” aka “Trauma Porn.” This is when an artist puts their lived experience, ie neurodiversity, being disabled, being a woman, being a person of colour, etc, on the stage for an audience to consume. Jeremy proposed that negative lived experiences all have inherent trauma within them and putting them on stage can prevent the artists from moving on in their lives, reinforcing their trauma by having to relive negative experiences night after night. Jeremy expanded on his proposition, suggesting that putting trauma on the stage can give audiences a false experience of having done something to fix the societal problem from where the trauma originated. ie “I’ve done something about that, I’ve watched a show!” Mining Personal Trauma For Art Jeremy remembered an experience in a workshop where a theatre director had asked the group to close their eyes and “think about the worst thing that’s ever happened” to them. Wanting to keep himself safe, Jeremy stood up and left the workshop. To all the directors who draw out trauma irresponsibly, Jeremy says, “It’s not your stuff to play with!” One of the delegates said, the important thing is “HOW people are [making work about trauma].” They offered the following questions for theatre makers to ponder on: “How am I able to contain [my trauma]? How am I able to have distance from it? Is it possible to sit in a place of safety and comment on those feelings from the outside?” Another delegate talked about the difference between personal and private, saying “When its private the person is still very much in it.” What happens to the audience when you put raw trauma on the stage? Someone said: “I need a bit of lived experience;” qualifying that as an audience member, this helps them resonate with the performer’s experience, which helps them connect with their own authenticity. Someone asked: “Do we have a duty of care to the audience?” Jeremy explained his view: “If you’ve not made sure you’re safe, you’re putting the audience in the role of caregiver.” Jeremy suggested that the audience in the role of caregiver feels an obligation to applaud, “to make the performer feel OK.” Drama Requires Conflict Jeremy proposed: “Drama requires conflict”. He asked; “Can you make a piece of theatre about your lived experience that doesn’t focus on the negative?” Someone from the congress asked: “What’s your experience of “negative?”” They argued that theatre can transform “negative” experiences, both in the performer and in the audience. They argued that if they themselves are comfortable with their own material, then it’s not a negative experience to play with it on stage. Someone else proposed that life is full of conflict and put forward that perhaps theatre can be a great space for exploring that. Clowns and Conflict Someone talked about the innocent quality of clown, which allows clowns to wade in and “nonchalantly” play with whatever conflict is present. This quality of innocence can paradoxically allow clowns to get closer to the knuckle of conflict. Someone spoke about a friend of theirs who has been in Gaza, clowning for children in refugee camps. They said it was their job is to distract from the conflict. Someone else spoke about clowning for the people of Grenfell tower, in the wake of the disaster - their job was to “help kids smile for 5 minutes,” in their experience, “giving people a reason to smile, gives faith and that brings hope”. Someone wondered whether this is the true power of the clown? Someone else mentioned the old adage: the clowns’ job is “to comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.” “What is the purpose of theatre?” Jeremy pondered:

Jeremy argues that theatre audiences are passive observers. He cited a video essay by Lindsay Ellis, where she talked about the Revolution Play Problem [I haven’t been able to find this video]. Apparently, Ellis spoke about how plays such as Hairspray, Rent, Les Mis and Hamilton have not changed how people engage with direct action. Jeremy pondered: “What’s the point of telling these stories?” Someone responded: “There’s no point to anything! We’re living in the wild west of existence!” They continued, suggesting that theatre allows us to explore “the shadow of humanity.” Someone else described a recent play session with a 5 year old, who said: “You stand there and shoot me and then we’ll do my funeral.” Kids are often naturally drawn to explore darkness through their play, perhaps it’s a human need? Someone else said: “We need the evil witch in the forest!” Bemoaning the “sanitisation of children’s theatre,” they reminded us that, “stories were created for communal responsibility.” “Where’s the pressure coming from?” Jeremy asked where the pressure comes from to make work about lived experience. He asked: Is it the funders? Is it the venues? Is it the artists themselves? He cited a Patrick Willems video essay - ‘Who Is Killing Cinema?’ [I haven’t watched it, but it’s here if you want to.] Jeremy told us how this video essay explores how cinema audiences are trained to like whatever the studios want them to like, but that can change, as the recent Barbenheimer phenomenon proves. Safety Measures Jeremy stated that just because he is neurodiverse and disabled, he doesn’t have to make work about it. He suggested, “If you want to make autobiographical work, protect yourself!” Jeremy spoke about exaggeration, mockery, parody and character work as good tools for personal protection. He described this as “telling an autobiographical lie.” A congress member talked about Le Coq’s mask theory, explaining that bouffon, clown and theatre can all be seen as masks; “When we wear a theatre mask it doesn’t touch the skin but it allows us to play - otherwise it’s the mask of death.” Jeremy finished with a plea for artists who want to work with their traumatic experiences to find a therapist and to shop around until they find the right therapist for them. My Tuppenceworth Jeremy’s provocations sparked a very lively debate. As a dramatherapist, it was heartening to witness a room full of clowns discussing trauma and safety for performers and audiences, bringing into consciousness the stuff that is often buried, unseen or ignored. The autobiographical solo show can be seen as a right of passage for many, but how many artists and directors understand how to safely work with trauma in the rehearsal room and on the stage? There was so much in this debate that I could comment on, but the thing that comes through for me most strongly is the theme of distance as a safety mechanism for both performers and audience. I appreciated the thoughts around the difference between private and personal and how to find a place of safety, where you can comment about your experience from the outside. I appreciated Jeremy’s thoughts around using theatrical forms such as exaggeration, mockery, parody and character work to create an “autobiographical lie” and Le Coq’s theory around the mask that can both protect and give freedom to the performer. There are many different therapeutic approaches to working with trauma, some seek to lead you away from the trauma, helping you to create new behaviours, new self-beliefs, new neural pathways, others create the conditions that allow you to look trauma straight in the eye and understand it cognitively or compassionately, thereby releasing the grip of it, others seek to help people process and release trauma through the body. What all the systems I’ve come across seem to have in common, is that they seek to help people create healthy distance between themselves and their traumatic experiences. Until that distance is obtained, trauma can stay in the body for years and can be re-triggered by a remarkably wide selection of obvious and seemingly innocuous things. As a life-long theatre maker and workshop leader, I can confidently say it’s nigh-on impossible to predict the things that might trigger people. What you might think of as a lovely, silly, playful group activity could be a living nightmare for someone who has childhood trauma coursing through their body. Learning how to work with trauma when it arises has been very useful in many situations. I’ve directed a lot of autobiographical clown shows, exploring big themes such as depression, eating disorders and grief. Because of my dramatherapy training, I’ve been able to spend time as part of the devising process, helping performers to process their trauma. Without this vital step, I’ve found that not only are they unsafe (ie liable to become re-traumatised), they are also too close to their material to be able to play with it. If a performer can’t play with their material, there’s very little life or space in it and the material can’t breathe. This has a knock-on effect with audiences - tightly held material can generate tension and discomfort and a weird sense of voyeurism in audiences. I’ve felt it myself, as an audience member; that uncomfortable sense of “Am I allowed to watch this?” which makes for a very complicated experience. I mean - it could be an interesting artistic choice to engineer this feeling of alienation, but I sense that often this is not what the artists are going for. Putting raw, unprocessed trauma on the stage is likely to trigger trauma responses in audience members. Some of the more responsible artists put trigger warnings on their work. Others have a quiet space where people can retreat to if it gets too much. I spent time with some of the artists I’ve worked with, co-designing after-show care packages for audiences, exploring ways of honouring, holding and containing their experiences and/or signposting for extra support. Because of financial constraints, rehearsal periods are often not long enough to fully process trauma to make it safe enough for performers and audiences. I would say, the healthiest way would be to slow everything down. Slow down the rehearsal process, put in breaks and integrate personal therapy. Directors should consider getting some trauma training or working alongside a therapist in the rehearsal room and it would be amazing if more people thought about the audience experience from beginning to end - what could you provide to make it safer for them? I really respect Jeremy’s position - why should people feel like they have to make work about their lived experience? But if they want to, I think this debate has a lot of useful questions to help people get conscious about why and how they want to make autobiographical work. Summing Up

I wholeheartedly enjoyed the contrast between these two sessions. Saskia’s practical and physical workshop and Jeremy’s theoretical and thinky debate offered two very different ways of connecting with the congress theme of identity. While Saskia was inviting us to use our personal experiences in our performance, Jeremy was giving us full permission not to. To me, this beautifully represents the spectrum of experience of clowns and applications of clowning today. There is no one way to clown and that should be celebrated! This event was a wonderful opportunity for clowns to find out about the work that other clowns do, to find their place in it all, to broaden their knowledge, to stretch out their limitations, to be inspired by each other and to play together. Long live the Clown Congress! Links

Comments are closed.

|

AuthorCreative research into the meeting point of clowning and activism Archives

May 2024

Categories |

ABOUT ROBYN

Robyn is a Bristol-based director, teacher and performer. With over 20 years experience she is a passionate practitioner of clowning, physical theatre, circus and street arts. She has a MA in Circus Directing, a Diploma of Physical Theatre Practice and trained with a long line of inspiring teachers including Holly Stoppit, Peta Lily, Giovanni Fusetti, Bim Mason, Jon Davison, Zuma Puma, Lucy Hopkins and John Wright.

Over the past five years she has been exploring the meeting point of clowning and a deep desire to address the injustices in the world. This specialism has developed through her Masters Research ‘Small Circus Acts of Resistance’, on the streets and in protests with the Bristol Rebel Clowns and in research residencies with The Trickster Laboratory. Robyn’s Activist Clown research has led to collaborations with Jay Jordan (Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination, France), Clown Me In (Beirut), LM Bogad (US), Hilary Ramsden (Greece) and international Tricksters; ‘The Yes Men’ (US). During the pandemic in 2020, Robyn set up The Online Clown Academy with Holly Stoppit and developed a series of Zoom Clown Courses. Robyn’s research, started during her Masters, has been exploring the meeting point of clowning and activism, online, in the real world and with international collaborators. With this drive to explore political edges of her work she has also dived back into the world of the Bouffon; training with Jaime Mears, Bim Mason, Nathaniel Justiniano, Eric Davis, Tim Licata, Al Seed and the grand master Bouffon-himself; Philippe Gaulier. Keen to explore the intersection of clowning and politics, Robyn is driven to create collaborative, research spaces, testing and pushing the limits of the artform to create new knowledge and methodologies for her industry and strengthen partnerships for future work. Some of her most recent collaborations and teaching projects have included the Nomadic Rebel Clown Academy (5-day Activist Clown Training), The Laboratory of the Un-beautiful (Feminist Grotesque Bouffon Training for Womxn Theatre Makers) and the Clown Congress (annual gathering of clowns, activists & academics collectively exploring what it means to be a clown in this current era) |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed