|

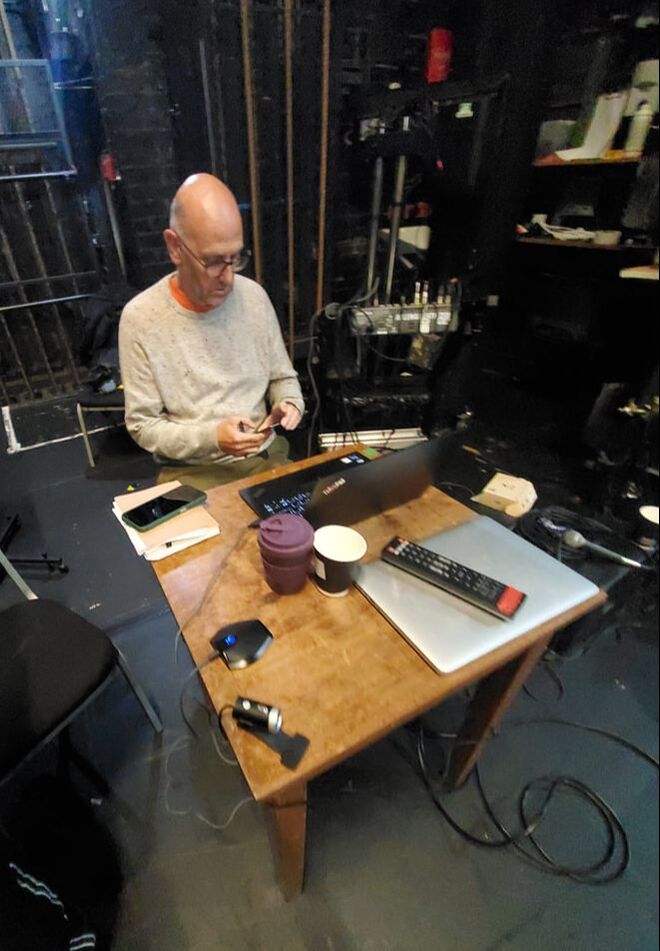

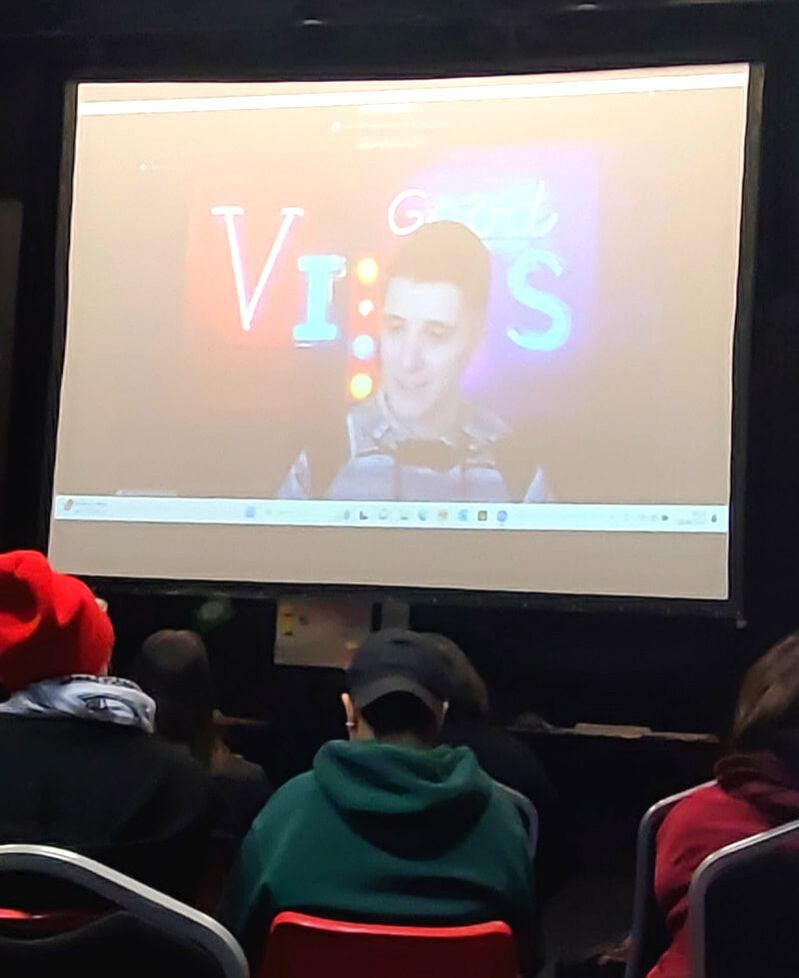

by Jan Wozniak On not knowing... It’s strange to be in my place of work, this theatre which I work in very week-day, on a Sunday. To do…what? Certainly not teach, which is what I usually do here. Clown? Learn? Play? Perform? Research? Work? A little of each, as it happens, and anyway, it’s OK for me not to know, either then or now. As I was on that Sunday morning, I am still, today, weeks later, contemplating what it means to be with the unknown, which is what Holly Stoppit asked us to consider on the first day of the Clown Congress. What it means for me as a teacher, as a clown, as a person, to not know. This seems consistent with the theme of this year’s Clown Congress, where we are exploring identity and clowning. And in exploring who gets to clown, and how they get to clown, who knows about clowning and gets to tell others? This also resonates with me in this place of learning. My students come here to learn, don’t they? To know something they didn’t know when they first arrive. We’ve (thankfully) moved on from ideas of knowledge ‘transfer’ to knowledge ‘exchange’. I firmly believe that I learn as much from my students as they do from me and I hope I facilitate for my students an opportunity to learn about their own experience of clowning within the history and contemporary practice of clowning. I tell them from day one that I don’t aim to teach them ‘how to clown’. Firstly, I don’t know! And secondly, this assumes that there is ‘a’ way to clown and I’m hoping that this weekend Congress brought many challenges to that assumption and many ways in which we might all explore clowning in the future. But students – and colleagues, who conduct their research – come here to ‘know’ don’t they? But how much do they – and we – admit that we don’t know? And how can clowning help with this? I aim to explore this in later research, but for now we share the doubts, the trepidation, the excitement of not knowing. And I certainly found much that I didn’t know and hadn’t contemplated fully before on day two of the congress. The student cohort at Bristol is (understatement warning!) not as diverse as it might be, and so my attendance at a Congress which set out to explore inclusive and diverse approaches to clowning means I am challenged, taken out of my comfort zone and give the opportunity to learn. First Session: Amelia from Quiplash Amelia from Quiplash joins by Zoom, and the session is facilitated in the room through Jon Davison. The decision to not be physically presented is reflected on by Amelia and Jon, as they recount moving from a panicked ‘Oh Shit!’ reaction to recognising that this highlights the very focus of the session: clowning from comfort as a radical approach. This initially seems, to me, to perhaps go against a well-established artistic narrative of being open to taking risks, of pushing oneself, of being uncomfortable, of moving beyond our comfort zones and even of Offending the Audience, as Peter Handke had it in the 1960s, one which is still dominant in many university drama departments. The true artist, in this narrative, is not interested in comfort, of self or audience, but of constantly challenging. Of course, we also always talk about creating safe and comfortable environments in which to develop such challenging work, but what do these safe spaces take for granted? Who might these exclude? Such approaches have been challenged more recently, for instance in the work of Tim Crouch, where there is a turn to caring for the audience. And what is made clear by both sessions today, is that this approach is only possible from a place of privilege (and assumed comfort) anyway. Amelia’s session begins with a description of the work of Quiplash, who explore radical inclusion in their work, and in particular their recent project, Unsightly Circus. This was an exploration of clowning and accessibility at the Barbican and later in the session we play the same games that Quiplash used in these sessions. In doing so, they explore a mash up of clowning and audio description, a word based tool used to describe the visual for blind and partially sighted individuals. Concentrating on the forms of clowning that tend to purposely use language in a playful or nonsense way, or to use no language at all, Amelia recounts how in fact, the first task was to find their own form of clowning. Again, comfort first is emphasised, with adaptation to follow. Access First is the important phrase here – this is the first thing they think about, rather than build something and then think about access. Not as an afterthought. This is actually familiar to me recently from designing teaching and assessments. For once, the institution’s initiative seems in line with positive change – they want to make sure that teaching and assessments are already designed for all, rather than have assessments which require alteration for those with different needs. So a good teaching session and a good assessment should already address inclusivity and different access needs, without having to think how they might be adapted. One way in which Amelia describes this happening is by adopting a mantra that ‘we are doing what we say we are doing’, even if that doesn’t look, sound or feel like we might expect it too. So ‘We’re doing it now’ is a usefu phrase here: we are clowning when we say we are clowning, even if no-one is laughing; we are aerialists when we say we are aerialists even if we’re not 10 feet off the ground. This reminds me of Bryony Kimmings assertion that the first step to being an artist is to say ‘I am an artist.’ In building a space that combines comfort and discomfort, Amelia explains how audio description can also help neurodivergent people – putting the vibe in a room into words can help them when they are not able to ‘read’ the room so easily. I am particularly intrigued by Amelia’s answer to a question about working with people with different, and potentially, conflicting access needs and how this can be managed. There is, of course, no easy answer, because each scenario presents its own questions and own solutions. Without knowing the specific different access needs, Amelia, rightly I think, does not want to propose a simple, catch-all solution. What is needed is to work from a space of comfort, leaving time and space to be comfortable and ‘safe’. Checking that people are working physically and mentally safety, for instance only putting on stage what someone is comfortable with, a message consistent with yesterday’s workshop. What I really liked about Amelia’s answer here that Quiplash prioritise there being no pressure to ‘make the thing’ or ‘finish the thing’. They care less about ‘completed’ work; more important is an environment that works for them – an environment of Access for All. After an interesting and stimulating introduction to their work, it’s time to play, as Amelia shared some of the games they used to explore clowning and audio description in the Barbican workshops. First we :explore how body and brain connected to movement and description can work together. We are invited to move about the space (moving potentially meaning just wiggling eyebrows) and on being asked to freeze, responding to the question ‘what are you doing’, with the first thing that comes to your mind. This is developed into working in pairs and small groups, moving together around the space and on freezing, answering what you are doing using a word that begins with a letter specified by Amelia. It’s perfectly OK, indeed perhaps preferable to have two different answers! We are then asked to reflect (with no judgment) how the words came to us: immediately? After a moment’s panic? Easily? With effort? In a rush? We also reflect on how differently we worked alone and with others – were we a leader or a follower? Amelia explains that this reflection allows us to think about how we might be relating to ourselves, our body, the act of description and to others. Once we can non-judgmentally identify and describe this, we can build performance material from this, creating character dynamics between the two trying to describe what they are doing. In a final game the clowns in the room are split into two groups and go round a circle giving a prompt to the next person: seven things...Again we are prompted to say the first seven things to come to mind, and not to rush, unless we want to. This is a useful exercise in which we can describe a clear ‘picture’ of a person, a character perhaps. As Amelia explains, in the games we have played, we have not yet achieved ‘Audio Description’, but these are useful games to incorporate in making work to move towards something useful. Second Session: Aerial Mel In the second session, Aerial Mel also highlights the assumption of comfort that can dominate artistic work that is not fully inclusive. They used games and exercises adapted from the works of Paulo Freire and Augusto Boal, approaches which I am generally familiar with, especially in challenging banking ideas of knowledge transfer and encouraging knowledge exchange through recognition of different forms of knowledge, but which are deployed here in what I find to be original, stimulating and challenging ways. As an able-bodied, white male, I am not able to fully feel the barriers that others may face in just attending a workshop, or a Congress like this – I cannot really ‘know’ the accommodations and changes that are needed for them to attend. But I can of course try, and Aerial Mel’s workshop gave me an interesting and challenging insight in to this as they explored accessibility through a series of games which highlighted these barriers. They begin by exploring how, of course, in many ways it is necessary to challenge what we ‘know’. Beginning with what seems a quite conventional introduction to a workshop, we are invited to dance to different genres of music. We, of course, ‘know’ how to dance to different genres of music, betraying embodied racist attitudes, as we head bang to some heavy metal and sway rhythmically to some soul and reggae. The workshop continues by exploring in small groups changing things about our physical appearance, for instance changing the position of a piece of jewellery, or rolling up a trouser leg. We are challenged to, without speaking, choose a person in the circle who will make the change, turn to face outwards and then, once the change has been made, to notice who and what has changed. This emphasises, for me, who thinks they are the leader, who thinks they are the centre of attention. We progress to three people changing three things and there is, from my position as a teacher trying to steal fun and useful exercises, an excitement about how this combines a number of elements my students might explore and enjoy: non-verbal communication, observation, fun! But as we progress to being all asked to change twenty things about ourselves, and then our time is suddenly cut short with no prior warning – because “The Arts Council has cut your inclusivity budget!” - the point of the exercise with relation to the experience of a disabled person trying to work in the Arts is made clearer. I have the privilege of being able to see this game as fun. As Mel says, though, “When a disabled person attends a workshop (or anything) they’ve already had to change 20 things”. Being asked to change ‘just one (more) small thing’ can be a huge ask, which can lead to individuals being overwhelmed and excluded.We finish by reflecting, as we did with Amelia from Quiplash, that there is no one easy answer to assure inclusivity as a priority and an attitude of Access First. The first step, though, is to ask what can I do to help you and to make you more comfortable. This sense of being overwhelmed is extended to a consideration of mental health conditions, where an exercise replicates what it is like to have ADHD. In a small group, one person volunteers to be the subject of the attention of 4 others. This exercise is safely and sensitively set up, with the subject being asked where on their body they are happy to be touched. Starting with one person asking questions about the person – name, where they are from etc – the subject is progressively given more attention and more to respond to: a second person touching them on a body part which they have to name; a third person asks factual questions, for instance, what is the capital of France; a fourth person asking them to identify the colour of things that are pointed to. I do not have ADHD and, again, initially see the exercise as another fun way of evoking in clowning students a state of bafflement, a state of not knowing and not being in control, which can be so useful in exploring the state of a clown. I use similar exercises which pile on cumulative requests, to participate in a sequence of names for instance, or to continually add another activity to a game. When Aerial Mel links this to the experience of ADHD, and then to the Citizenship Test for refugees, the stakes of confusion, of getting an answer wrong, are exposed as much higher for others than for me, and I am reminded again of my privilege when I clown, where I can enjoy overwhelming sensations and not feel attacked in a comfortable and safe clowning workshop. We finish by reflecting, as we did with Amelia from Quiplash, that there is no one easy answer to assure inclusivity as a priority and an attitude of Access First. The first step, though, is to ask what can I do to help you and to make you more comfortable. On still not knowing

I return to the theme of not knowing that has been occupying me so much. As a philosophy of education, perhaps not knowing is as much a privilege as knowing. I am reminded of Bourdieu’s concept of habitus, the embodied way we each live our lives according to the learning we have had since birth, whether physical, psychological or cultural. Anyone who doesn’t know a situation (a refugee in a new country, a working-class student at university) doesn’t ‘know’ how to behave. For me to suggest that not knowing is a fun and productive approach to learn is to work from a place of privilege. I have to make sure that this can happen from a place of comfort. But what if we at least embraced our not knowing, our ignorance, more, just a little more? In exploring this further, I aim to return to the work of Jacques Rancière, whose book, Ignorant Schoolmaster, explores and advocates how teachers ignorant of their subject matter can still facilitate student learning. There is a saying amongst Further Education teachers, that you only need to be one page ahead of your students to teach effectively. I like to adopt Rancière’s suggestion that a teacher always works with students to adapt this saying to being on the same page as students. This is a furthering, in my view, of Freire’s and Boal’s work on education, democratising and talking about exchange, rather than a banking model where we acquire knowledge and put it away safely. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorCreative research into the meeting point of clowning and activism Archives

May 2024

Categories |

ABOUT ROBYN

Robyn is a Bristol-based director, teacher and performer. With over 20 years experience she is a passionate practitioner of clowning, physical theatre, circus and street arts. She has a MA in Circus Directing, a Diploma of Physical Theatre Practice and trained with a long line of inspiring teachers including Holly Stoppit, Peta Lily, Giovanni Fusetti, Bim Mason, Jon Davison, Zuma Puma, Lucy Hopkins and John Wright.

Over the past five years she has been exploring the meeting point of clowning and a deep desire to address the injustices in the world. This specialism has developed through her Masters Research ‘Small Circus Acts of Resistance’, on the streets and in protests with the Bristol Rebel Clowns and in research residencies with The Trickster Laboratory. Robyn’s Activist Clown research has led to collaborations with Jay Jordan (Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination, France), Clown Me In (Beirut), LM Bogad (US), Hilary Ramsden (Greece) and international Tricksters; ‘The Yes Men’ (US). During the pandemic in 2020, Robyn set up The Online Clown Academy with Holly Stoppit and developed a series of Zoom Clown Courses. Robyn’s research, started during her Masters, has been exploring the meeting point of clowning and activism, online, in the real world and with international collaborators. With this drive to explore political edges of her work she has also dived back into the world of the Bouffon; training with Jaime Mears, Bim Mason, Nathaniel Justiniano, Eric Davis, Tim Licata, Al Seed and the grand master Bouffon-himself; Philippe Gaulier. Keen to explore the intersection of clowning and politics, Robyn is driven to create collaborative, research spaces, testing and pushing the limits of the artform to create new knowledge and methodologies for her industry and strengthen partnerships for future work. Some of her most recent collaborations and teaching projects have included the Nomadic Rebel Clown Academy (5-day Activist Clown Training), The Laboratory of the Un-beautiful (Feminist Grotesque Bouffon Training for Womxn Theatre Makers) and the Clown Congress (annual gathering of clowns, activists & academics collectively exploring what it means to be a clown in this current era) |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed